Psychiatric treatments have a spotty historic record, with numerous dubious methods employed over the centuries, particularly across Europe. As scientists experimented on patients, they often resorted to increasingly reckless treatments, like lobotomies, electroconvulsive shock therapies, and more.

An unusual method of treatment gained some attention on Twitter in May 2023. User @gruhuken wrote, "I found out today that in the 1800s they tried calming down mania patients by putting them in a big chair swing and spinning them around very quickly until they passed out."

I found out today that in the 1800s they tried calming down mania patients by putting them in a big chair swing and spinning them around very quickly until they passed out pic.twitter.com/DdYVwKdIou

— will 🦇 (@GRUHUKEN) May 18, 2023

This was indeed a method used in the 19th century with patients who suffered from mania and other psychiatric conditions. The method was developed in part by English physician Joseph Mason Cox, who worked largely with mentally ill patients.

"Mania" in the 1800s was conceptualized as "an agitated psychotic state." The Cleveland Clinic defines it today as a condition in which "you display an over-the-top level of activity or energy, mood or behavior. This elevation must be a change from your usual self and be noticeable by others. Symptoms include feelings of invincibility, lack of sleep, racing thoughts and ideas, rapid talking and having false beliefs or perceptions."

In his 1804 book, "Practical Observations on Insanity," Cox discussed the method and its results in a section titled "Swinging." Describing it as a "moral and medical mean in the treatment of maniacs," he wrote:

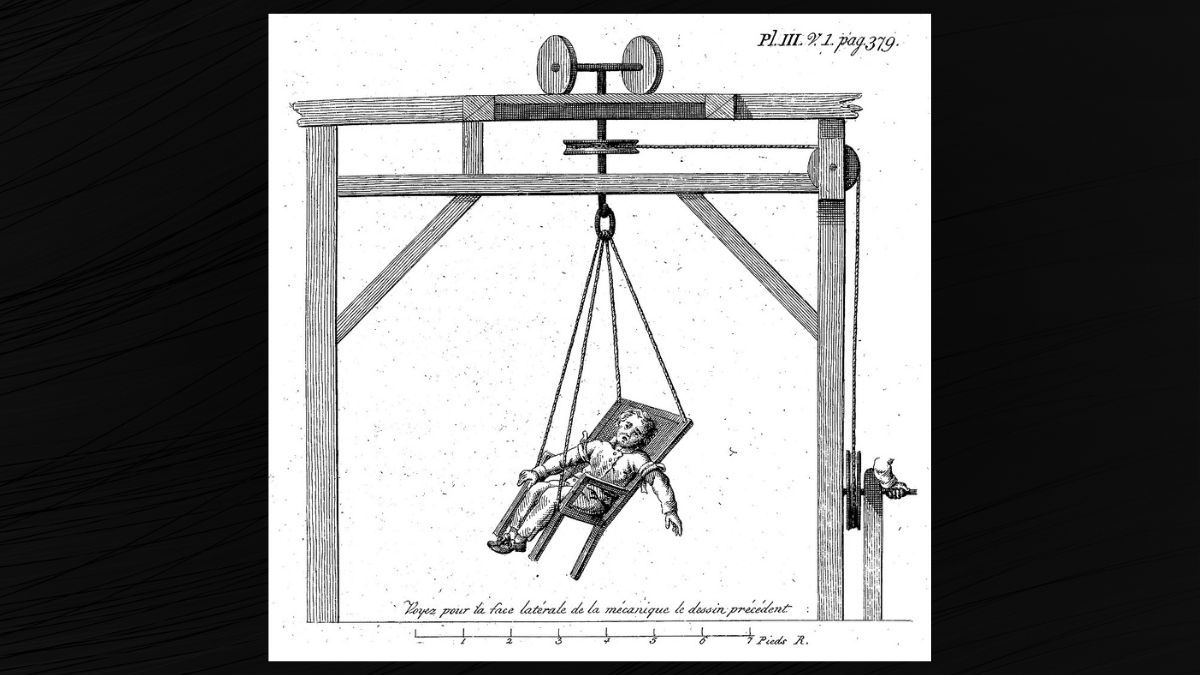

[...] [The circulating form] is easily constructed by suspending a common Windsor chair to a hook in the ceiling, by two parallel ropes attached to the hind legs, and by two others passing round the front ones joined by a sliding knot, that may regulate the elevation of the patient when seated, who, besides being secured in a strait waistcoat, should be prevented from falling out of the chair of the attendant pushing or pulling the extremity of the projecting arm, with greater or less force, each time it circulates, but by a little very simple additional machinery any degree of velocity might be given, and the motion communicated with the utmost facility. Thus by means of the chair or the bed, the patient may be circulated in either the horizontal or perpendicular position.

He wrote that such a movement would render "the system sensible to the action of agents, whose power it before resisted."

He also detailed the lulling effects of such motions: "One of its most valuable properties is its proving a mechanical anodyne. After a few circumvolutions, I have witnessed the soothing lulling effects, when the mind has become tranquilized, and the body quiescent; a degree of vertigo has often followed, and this been succeeded by the most refreshing slumbers."

Cox, however, noted the adverse effects of this practice: "One of the most constant effects of swinging is a greater or less degree of vertigo, attended by pallor, nausea, vomiting, and frequently by the evacuation of the contents of the bladder."

The Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh described Cox's methods, as well, including that doctors could decide how fast they wanted the chair to rotate, based "on a scale between nausea and 'unmerciful evacuation'."

In a 2013 paper published in the Frontiers of Psychiatry journal, a group of German researchers revisited the effectiveness of this method. They noted that Cox's spinning chair was "mostly applied to patients suffering from mania, other forms of high agitation or catatonic stupors with the aim to calm them and put them into a milder condition."

They added that retrospective studies of the method documented "abusive applications" in how it was used, even as it may have positively influenced studies on the effects of vertigo, the construction of the Bárány chair that is used in aerospace training, and carnival rides.

The 2013 study tested a version of the spinning-chair method and concluded, "that vestibular stimulation on a 3-D spinning chair has a specific impact on mood states and may be used for studying the well-known, although barely studied, link between the vestibular system and the emotional brain," while emphasizing that further research was needed.

Andrew Scull's book, "The Most Solitary of Afflictions: Madness and Society in Britain 1700-1900," detailed how William Saunders Hallaran, described as an "Irish mad-doctor," designed a seat that "'supports the cervical column better, and guards against the possibility of the head in the vertiginous state from hanging over the side [sic]'." Hallaran and Cox were able to create machines that were capable of "reducing the most violent and perverse to a meek obedience."

And similar practices were not just limited to the U.K. American physician Benjamin Rush (who died in 1813) developed a rotational chair as a treatment for psychotic patients, believing it helped aid circulation to their brain. Rush also was a statesman who signed the Declaration of Independence and became a pioneer in the field of mental health.

Cox's chair method was also widely adopted in Europe in the first few decades of the 19th century, though it fell out of favor soon after, according to a 2005 paper in the History of Psychiatry journal. Cox was not the only scientist experimenting with rotation therapy. According to another History of Psychiatry research paper, before Cox's work was translated into German, Ernst Horn, a psychiatrist at the Charité in Berlin, introduced rotation therapy there first on a bed in 1807, then on a chair at an unspecified later date.

Given the long documented use and experimentation around such a practice, we rate this claim as "True."