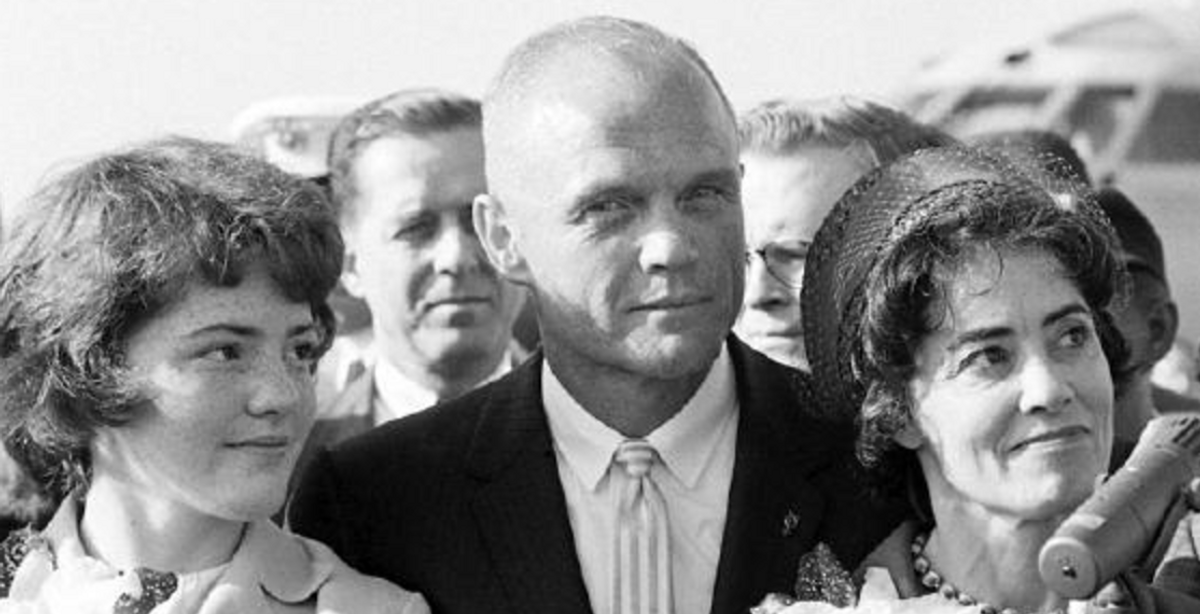

Most Americans are familiar with the exploits of John Glenn, a former U.S. Marine Corps pilot who, as one of the original Mercury 7 astronauts, was transformed into a national hero after becoming the first American to orbit the Earth on 20 February 1962. Later in life he represented Ohio in the United States Senate for twenty-four years, and in 1998 he became the oldest person to go into space when he flew on a Space Shuttle Discovery mission in 1998.

Much less well known is John Glenn's wife, the former Annie Castor, whom Glenn had known since childhood and married when he was a 21-year-old combat pilot during World War II. In February 2012, the fiftieth anniversary of Glenn's orbital flight prompted CNN contributor Bob Greene to pen an article about the Glenns' lengthy marriage (then at 68 years and counting) and Annie's long battle to overcome a terrible stuttering problem which had she had struggled with since she was a little girl, an affliction she finally managed to overcome at the age of 53.

Annie Glenn began speaking out publicly about her lifelong struggle with her speech impediment in the early 1980s, discussing the subject on national television and in the press, crowning her achievement by making speeches on behalf of her husband as he campaigned for the 1984 Democratic presidential nomination. A 1982 Los Angeles Times article on the subject reported that:

Annie Glenn is one of the country's estimated 2 million people who suffer what may be the most misunderstood disability: stuttering.

Until she underwent a new form of intensive, live-in treatment three years ago at the Communications Research Institute at Hollins College in Roanoke, Va., Mrs. Glenn could not speak well enough to call the plumber, order a meal in a restaurant or go by herself with her injured child to a hospital emergency room, much less give a campaign speech for her husband.

Although she still stutters slightly and speaks haltingly, Mrs. Glenn can perform all those once impossible tasks. She even gives campaign speeches, maybe not with as much polish as other wives, but certainly with more pluck.

At a private athletic club in Cleveland, 150 people attending the annual meeting of the Cleveland Hearing and Speech Center sat in silent attention at their dinner tables as their speaker told them something really quite remarkable.

"For the first time in my life," said Annie Glenn, age 62, "I can carry on a conversation."

It wasn't so long ago that Mrs. Glenn, classified as an 85% stutterer, would have found it impossible, even, to travel by airplane from Washington to Cleveland by herself unless she wrote down what she wanted for the airline employee at the ticket counter. She told the audience of such an experience and how the men wrote notes back, thinking she was deaf.

During the slow, agonizing process in which stutterers try to force out sounds, often with their hearts beating at an accelerated rate, their palms sweating, their cheeks blushing and their heads bobbing, Mrs. Glenn has been laughed at. Store clerks have reacted by pointing an index finger at the head and moving it in circles (the "crazy" sign), or by asking if she were cold when her jaw would quiver, or saying quite simply, "Lady, I haven't got all day."

Sometimes Mrs. Glenn would walk away rather than continue the ordeal of shopping.

Her husband had to make all the telephone calls to repairmen and friends. Her neighbors had to call the doctor when her children became ill and go to the hospital with her to talk with the doctors.

Mrs. Glenn had undergone several traditional speech therapies but experienced little or no improvement until she enrolled herself for two different sessions at the Hollins Institute, most recently in September of 1978. The therapy lasts 11 hours a day for three weeks.

After taking the therapy twice, Mrs. Glenn still sees a therapist twice a month at Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, and she practices every day — on the telephone. She makes several calls every morning. There is a sign next to her phone at home that says "Take a full breath, relax your throat, keep the sound moving."

"She talks to her buddies all over the world," John Glenn said, pretending to resent the phone bills. "This is a dramatic, new life for her."

A 1983 Associated Press article on the same subject read (in part):

For 53 of her 63 years, Annie Glenn was a prisoner of her own tongue, a stutterer who tripped over eight out of every 10 words, relying on facial expressions to make a point. She disciplined her two children, she recalls, "with my eyes and my hand."

Today, the wife of Ohio Sen. John Glenn has broken through a sound barrier. "Being able to talk to people is something I could never do," she says. "My life is like a dream."

In numerous conversations [on the campaign trail] throughout a day that started before dawn and ended long after sunset, [the couple] talked about Mrs. Glenn's newly acquired ability to speak fluently and the impact of her lifetime of stuttering on their marriage, children and career.

"John would make all my telephone calls," Mrs. Glenn says, shooting a stern look at her husband as he reached for a third chocolate bar. "I would try to go shopping but couldn't ask the clerk what I wanted, so I would hunt and hunt. A lot of the time I'd go out of the store empty-handed because I couldn't find what I wanted."

It was in 1974, after Mrs. Glenn enrolled in a speech program at Hollins College near Roanoke, Va., that her speech improved noticeably. But she didn't keep up the daily therapy sessions or return for refresher courses, and she regressed.

After a second session at Hollins and a program of daily therapy, Mrs. Glenn is making speeches.

"Annie was never silent to me," [Glenn] says. "But to see her at this age branch out to things she was interested in but could never participate in ..."

John and Annie had been married for 73 years when the former passed away in 2016 at the age of 95. Annie herself reached the century mark before she died in May 2020 of complications from the COVID-19 coronavirus disease.